Lithuania is committed to reducing the number of adults with disabilities placed in social care by 40% before 2020, and the number of children in such arrangements should decrease by 60%. Yet data show that structural investment from the European Union, vital for this process, got channeled into creating slightly more comfortable environments rather than alternative arrangements.

Healing mental disorders with concrete

Lithuania is committed to reducing the number of adults with disabilities placed in social care by 40% before 2020, and the number of children in such arrangements should decrease by 60%. Yet data show that structural investment from the European Union, vital for this process, got channeled into creating slightly more comfortable environments rather than alternative arrangements.

Last year multiple scandals shook up the system of institutional care, as several minors, living in social care institutions, died allegedly due to negligence. Still, three ministries responsible for ensuring that children with mental and psychological disorders get the services they need currently have no incentives to cooperate for the sake of reforms. However, the European Commission is promising that in the future states would have to repay any investment used for postponing rather than encouraging the placement of people with disabilities in community homes.

Rasa (name has been changed), who sent her then-underage son Robertas (name has been changed) to a social care institution (the name of the institution is known to the author), says she could not take care of the boy at home. Robertas, who has an autism-spectrum diagnosis and a severe mental disability, is now an adult. Yet his condition is by no means getting better in social care – he often suffers from seizures. The environment of the institution and relationships with other residents, as well as strict confinement methods (belts and handcuffing) make him tense. “That department [of the institution] is no good for him – someone with depression lies nearby, and others are halfway as challenged. My son has to lie there tied to his bed, because he breaks his healthier roommates’ things,” Rasa regrets.

Last year 646 people lived in social care homes for children and youth with disabilities. Human rights organizations emphasize that it is not enough to give these institutions a facelift – the model of service provision has to change.

Money was available

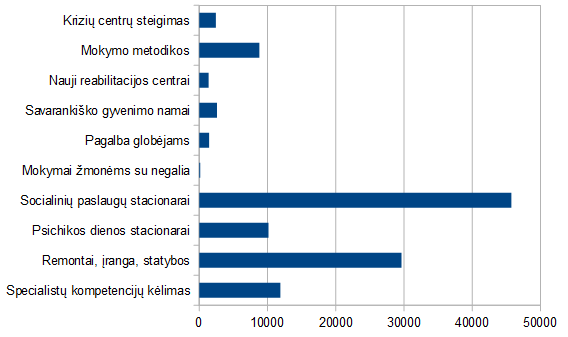

When it comes to identifying what people with disabilities and their families lack the most, the Ministry of Health (MoH) was able to learn about it from the Feasibility study for optimizing mental healthcare services, which MoH commissioned. According to the authors’ estimations, comprehensive reform would require about 28.5 million euros over the period of EU structural assistance. Calculations for this article, based on data in the Ministry of Finance’s website esparama.lt, show that around 60 million euro was spent on measures related to mental health (see chart).

Spending of EU funds on: crisis centers, training methodologies, new rehabilitation centers, independent living homes, assistance to foster parents, training for people with disabilities, social care facilities, day-patient facilities, renovation/equipment/construction, training professionals (in thousand euros, list not finite)

The authors of the feasibility study criticized the fact that the government does not make use of experience of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to create a new type of flexible services, and pointed out a lack of social workers and specialists in peripheral areas. Despite these findings, cooperation with NGOs in the previous period of EU structural assistance was not funded. Following up on the implementation of recommendations provided in the feasibility study and elsewhere could have been possible using nearly 145 thousand euro of EU funds and 25.6 thousand euros of state funds for evaluation and monitoring. However, the description of the measure requires the project to be implemented without partners (including NGOs).

In addition, the quality of evaluation and monitoring of mental health services materialized as repairs of premises, or purchases of office equipment, furniture, computers, and a vehicle. According to the project submitted, State Mental Health Centre will assess no less than 97 mental health institutions better when it has new furniture, a car and equipment, because staff will be able to carry out field visits.

The Ministry of Social Security and Labor (MoSSL), responsible for social care, has disbursed around 20 million euros for projects under its supervision, of which EUR 7.5 million was invested in construction, renovation and purchase of equipment to residential homes. In response to an inquiry, MoSSL specialists explained that it is necessary to help “prepare for the licensing of social care institutions”. The goal to move people with disabilities into community-based care with the help of EU funds was not raised, according to the experts said.

This trend is not unique to Lithuania. The Mental Disability Advocacy Center (MDAC) found that millions of euros are still spent on building and renovating social care institutions, against strategic commitments of the EU. The European Disability Strategy 2010-2020: A Renewed Commitment to a Barrier-Free Europe commits to using structural funds for development of community-based services, training of staff and adaptation of infrastructure. In May last year, the EU Ombudsman Emily O’Reilly undertook a special inquiry on the structural assistance going against the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Member States justified themselves saying that it would not be more humane to allow current residents of institutional care to stay in gloomy present while they wait for better future. On the other hand, the European Commission admitted to failing to control the flow of funds and promised that the states which continue to finance institutional care will have to return the funds.

Unsynchronized links

According to the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, states should create deinstitutionalization plans to avoid making mistakes in the future. Lithuania has one – the Action Plan on Transition from Institutional Care to Family and Community-Based Services for People with Disabilities and Children Deprived of Parental Care, 2014-2020. Institutions do change – care institutions decrease in size, and crisis intervention services develop within the healthcare system.

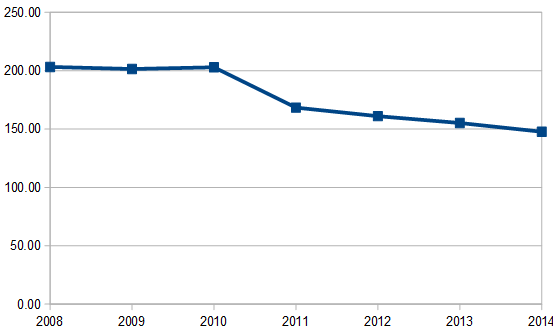

Large numbers of residents and insufficient attention to individuals is the main argument against large residential institutions, which serve as places of residence, hospitals and communities for people with disabilities (see the average number of residents in Lithuanian institutions in the chart).

Apart from that, a renowned child psychiatrist, mental health expert Dr. Dainius Pūras, as well as human rights organizations, including Human Rights Watch, are critical of small institutions, too. “How can one provide quality care for 10-12 children who are not their own? I’m not talking about pseudo-family-households, where care institution buildings remain the same, only residents are divided among different households and drink tea together in the evenings,” the expert says. According to Pūras, in private conversations public officials divulged their greatest fear – that abandoned children would be adopted by same-sex couples. This, the expert says, apparently sounds worse to them than physical and sexual abuse in institutions or excessive movement restrictions.

Services for people with mental and intellectual disabilities are divided among three ministries, because different bodies have to take care of these people’s everyday needs, socialization, and healthcare. Experts of the MoH explain that their ministry spent EU assistance on addressing the most pressing needs in their sector. “Having established new psychiatric day-patient departments in hospitals, patients and their families no longer have to travel to other cities and regions, where psychiatric hospitals providing day patient psychiatric services are located. Now patients have an opportunity to stay in their home environment, close to their family and normal environment,” said Virginia Karalevičiūtė, chief specialist at the ministry’s European Union Support Division.

However, this is only a part of the picture. Klaipėda National Hospital is one of the beneficiaries of EU funding. Its example shows what happens when only the health segment receives a boost. “Our division treats children who are difficult to deal with,” Teresė Ramanauskienė presents the hospital’s services. “As long as they are inside, in a structured environment, with people who engage with them and are kind to them, they calm down. I asked one child, “How come you’re a nice guy here, but in your care home you behave so bad?” His response was, “I treat others the way they treat me”. It is common that they are angry at the whole world, they feel rejected and abandoned. It is very sad.” Almost one-third of the patients in this depsrtment come from institutional care homes.

Welfare of people with disabilities is not among success indicators

The Lithuanian framework for reporting on EU assistance requires keeping track of how many people with disabilities benefit, but the number is not divided by type of disability. When MoSSL used EU funds to support professional reintegration of people with disabilities, employment was set as a performance indicator. An evaluation of EU funding shows that such indicators do not encourage authorities to take the risk of working with people who are the most distant from the labor market, such as institutional care residents. Indicators like transfer from foster home to independent living arrangements are nowhere to be found.

According to reports, construction and reconstruction of buildings where services to people with disabilities are provided fared much better in terms of performance indicators than finding participants with disabilities for various activities. An operational program set the target to 144 building projects, and project applications raised the number to 165. For example, to access the implementation of an EU-funded measure to promote better integration of people under risk of social exclusion and their families into the society and labor market, the following indicators apply: the number of constructed and renovated buildings, and the number of direct beneficiaries. The latter amounted to 390 thousand, according to the plans set in operational programs, but in specific projects, the plans were raised to 457.7 thousand beneficiaries with disabilities. If targets are set like this, investing in ‘concrete’ (construction and renovation) is the most convenient, since anyone who uses services or lives in a renovated building will be a beneficiary, even if the investments do not comply with the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. It will not be difficult to report quantitative results.

Dr. Pūras believes that it is time that the government takes responsibility for deinstitutionalization programming, because individual ministries have no incentive to cooperate. When asked about the main weaknesses of the system, Indrė Bakanienė, head of the Habilitation/ Rehabilitation and Nursing Division at the Children’s Rehabilitation Hospital “Lopšelis“, concludes, “There is no need to invent the wheel. There are systems in place in Europe, all we need is to adopt and adjust them. Like in the West, we need to close inpatient facilities and stop pretending that mud and paraffin therapy can be used to treat autism or mental disorders. We must provide services in the community where the child lives, and watch what he/ she needs.” The hospital she works for is always overbooked, because rehabilitation must compensate for what the children do not receive in the education system.

Bakanienė complains that under the current provisions on rehabilitation, even institutions working with children with physical or mental disabilities are obliged to provide services that are irrelevant to their patients, such as magnet therapy. This requires purchasing irrelevant equipment. How does one get out of this situation? Probably by writing another project to receive support for equipment and renovation.